Revolutionary Ingredients

Job‐Makers (30 – 44 year olds)

Job‐Makers have been working for an average of 15 years. They tend to be married, have small families and their savings rise, on average, every year. They typically refrain from upsetting their idyllic sweet spot in life by igniting revolutions. The businesses they started and the jobs they gave rise to will be eventually be filled by the Youth generation. Egypt has 15.8 million Job‐Makers.

Youth (15 – 29 year olds)

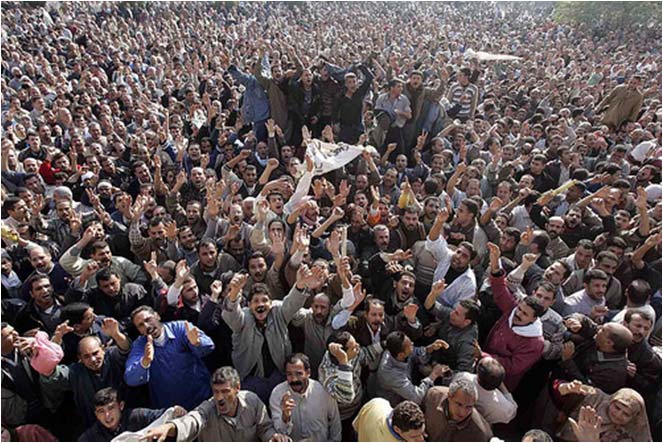

Our revolutionary core have just completed their education – or are about to do so – and are looking for a decent job that will allow them to dress well, buy a car, find a mate, buy a house, get married and start a family. The likelihood of these Youth finding a job depends to a very large extent on the size of the generation that preceded them (the Job Makers). Egypt has 23 million Youth.

ΔYouth ( 15‐year rate of change in Youth population)

A large but stable Youth population will eventually find employment. Jobs will be created to match the demand for them by Youth who want to work. Wages may fall in this equation, but the Youth will be employed.

A rapidly increasing Youth demographic is dangerous for it invariably grows much faster than new jobs can be created. The 23 million Youth in 2011 exceeded the 1996 total by 7.2 million, resulting in a 46% increase in the Youth demographic over 15 years.

Even if Mubarak were a modern, growth‐oriented leader who embraced economic stimulation via lower taxes, easier monetary policy, infrastructure spending, currency devaluation and subsidized trade, he would have been unable to significantly repel the tide of unemployment.

Japan’s solution, followed by many other Asian countries, was over‐employment; hire three workers to do the job of one and pay them peanuts. Unemployment rates fall, but the three workers are miserable and just as prone to revolutionary tendencies as the unemployed.

ΔYouth ( 15‐year rate of change in Youth population)